Crohn’s disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). As the name implies, IBD is characterised by chronic intestinal inflammation particularly, swelling due to cellular processes. The other major IBD is Ulcerative Colitis (UC).

Introduction

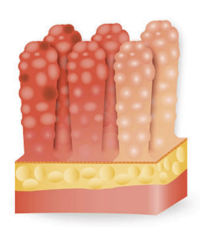

In Crohn’s disease the characteristic feature is inflammation of the bowel which may extend through the entire thickness of the intestinal mucosa. It most commonly affects the lower small intestine (ileum) and the large intestine (colon), but may involve any part of the digestive tract from the mouth to the anus and the disease can have extra intestinal manifestations. Patients with Crohn’s disease may experience abdominal pain, diarrhoea and a range of other symptoms including fever and weight loss.

The disease occurs about equally in men and women and usually appears for the first time in those aged 14-24 years, but can occur in people of any age.

Causes

The cause of Crohn’s disease remains unknown, although genetics may play a part as people with a family history of IBD have been shown to be at an increased risk of developing the disease. About 20% of people diagnosed with Crohn’s disease have a blood relative (especially a sibling and sometimes a parent or child) with some form of IBD. Apart from genetic predisposition, certain chromosomal markers have been found in the DNA of patients with Crohn’s disease. Cigarette smoking may also contribute to the development and / or exacerbation of the disease.

The inflammation in Crohn’s disease has, in the past, thought to have been related to autoimmunity. The immune system is a defence system in the body composed of cells and proteins that act to protect the body from harmful infections and foreign bodies. Under normal circumstances, an invading microbe, pathogen or foreign body is recognised by the immune system which then mounts a retaliatory response. Specialised cells target the ‘non-self’ cells or proteins and either destroy or expel them. Inflammation of the related cells and tissues occurs as part of this process.

The immune system is usually able to differentiate between food, good bacteria and other normal bowel components and the harmful microbes, pathogens and foreign bodies. In people with Crohn’s disease however, the immune system seems to overreact even to normal substances and bacteria, stimulating a response where the white blood cells invade the intestinal lining and produce inflammatory cytokines leading to chronic inflammation, tissue swelling, injury and ulceration.

The precise cause of this abnormal immune response is unknown although the existence of a specific infectious agent has not been disproved.

Infection research

For years, research has been ongoing to find an infectious cause for Crohn’s disease. A growing body of evidence suggests that a bacterium called Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) may infect a genetically susceptible subgroup of the population resulting in Crohn’s disease.

Researchers here at the Centre for Digestive Diseases have been instrumental in revealing this possibility and remain at the frontline of international research in this area.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms associated with Crohn’s disease include abdominal pain (often in the right iliac fossa) and diarrhoea. Rectal bleeding, mucus discharge, loss of appetite, fever and weight-loss may also occur along with other non-specific symptoms like fatigue, joint pain and skin problem. Children with Crohn’s disease may suffer delayed development and stunted growth.

Being a chronic condition, patients with Crohn’s experience intermittent flares where symptoms and disease intensity can range from mild to severe. Flares are interspersed with periods of remission where the disease is not active. Patients may feel well and be symptom free for substantial periods of time.

Despite the need to take medication for long periods with possible, occasional hospitalisations, most people with Crohn’s are able to live with the condition, holding jobs, raising families and functioning normally.

Complications

Complications in Crohn’s disease classically result from chronic, uncontrolled inflammation and usually manifest only in severe disease. Frequent inflammation of the intestinal walls leads to stiffening and narrowing of the bowel lumen causing strictures and intestinal obstruction. Tears may develop at the anus resulting in fissures and in some cases, fistulas can develop. A fistula is a connecting tunnel between two or more sections of the bowel or between the bowel and another nearby structure like the bladder, vagina or the skin near the anus. The usual place for a fistula is near the anus and this is known as perianal fistula.

Nutritional complications are common in Crohn’s disease, with poor absorption leading to deficiencies of important proteins, calories and vitamins. Other complications associated with Crohn’s disease include arthritis, skin problems, inflammation of the eyes and mouth, kidney or gall stones and liver disease.

These complications often resolve with appropriate management of the inflammatory process, but sometimes require separate treatment.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of Crohn’s disease can be challenging due to the similarity of its symptoms with other GI disorders such as UC and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

The medical history along with stool, blood tests and certain laboratory investigations (which may show anaemia, inflammation and malabsorption) can raising clinical suspicion and be sufficient for a preliminary diagnosis, but to be certain the gastroenterologist may order further tests such as plain x-rays, barium x-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), colonoscopy and panendoscopy.

For a definitive diagnosis, it is recommended a colonoscopy is performed and biopsies (tissue samples) are collected from the bowel to confirm Crohn’s histopathologically. Histopathological examination involves staining and examining a slice of the specimen through a microscope. The pathologist is looking for changes at the cellular level that confirm Crohn’s disease. In some cases, treatable secondary infections can aggravate or be the cause of inflammation, therefore samples of luminal fluid may also be taken for investigation during the colonoscopy.

Treatments

Treatment for Crohn’s disease depends on the location and severity of disease, complications and response to previous treatment. The goals of current treatment strategies are to control inflammation, heal the damaged tissues, relieve symptoms and correct nutritional deficiencies.

Currently there is no cure, but treatment can help control the disease. People with Crohn’s disease may need medical care for an extended period with regular doctor visits to monitor the condition.

Treatments that may be used in the management of Crohn’s Disease include:

- Anti-inflammatory agents:

- Aminosalicylates: The class of drugs known as aminosalicylates (5-ASA) are used to treat mild to moderate inflammation in Crohn’s disease and are usually combined with other medications. Aminosalicylates work by controlling inflammation and may be effective at inducing and maintaining disease remission. This category of drug has also been shown to have activity against MAP and is currently under further investigation.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Omega-3 Fatty Acids are also anti-inflammatory agents which can be useful in therapy of IBD.

- Immunosuppressive agents:

Corticosteroids:

-

- Some patients take corticosteroids to control inflammation. These drugs non-specifically suppress the immune system and are used to treat moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. They treat the acute stages of disease by dramatically reducing fever and diarrhoea, relieving abdominal pain and tenderness and also, improving appetite and general sense of well-being. Long-term corticosteroid therapy can induce serious side effects, most notably skin and bone changes and greater susceptibility to infection. For this reason, short-term steroids can be very useful but long term steroids are generally avoided.

- Immunomodulators:

- Immunomodulators are medications that work by specifically blocking the immune reaction that contributes to the inflammation in Crohn’s disease, helping to improve overall clinical status, decrease the need for corticosteroids and maintain remission. Their action may not take effect for 2-6 months and their use must be closely monitored for potential side-effects. This category of medications may have anti-MAP activity.

- Biologic Agents:

- Biologic Agents are medications that they be prescribed to treat severe Crohn’s disease that is non-responsive to other forms of treatment.

- Antibiotic agents

- Koch’s postulates have now been fulfilled proving that, in a subset of patients, the mycobacterium MAP is involved in the development and persistence of inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Anti-mycobacterial agents specifically targeting this causative pathogen have shown success in inducing remission (at times long term) in severe disease.

- The Centre for Digestive Diseases is a leader in this area of research and recently an Australia-wide trial has been completed against MAP, the results of which have shown that the highest reported remission can be achieved with anti-MAP therapy. However due to limitations within the trial, the long term maintenance section cannot be currently accepted as having any clinical significance.

- Surgery

- Whilst surgery does not cure the disease, it is a tool for management of serious complications including strictures, obstructions, fistulae or overwhelming disease unresponsive to treatment. The patient makes the decision of pursuing surgical intervention after close consideration of the information given by doctors, nurses, other patients and support groups.

- Nutritional supplementation

- Nutritional supplements or special high calorie liquid formulas may be recommended especially, in children with impeded growth and development. A small number of patients with absorption problems, malnutrition or severe disease may require enteral feeds.

- Further research

- Many Crohn’s Disease treatments are being researched including the Crohn’s MAP Vaccine. The Centre for Digestive Diseases has in the past contributed to some of the key research areas in Crohn’s disease and is actively involved in research in this area. For further information, please look into our research section.

Further Reading

Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. (2018). Position Statement: Crohn’s Disease and Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP). Published online. Site accessed 09/12/2020 https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/MAP.final%202018%20%281%29.pdf

Crohn’s MAP Vaccine Website: http://www.crohnsmapvaccine.com/about/friends-supporters/

Johns Hopkins Fact Sheet Crohn’s Disease. Accessed online at: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/crohns-disease

Lamb, C.A., Kennedy, N.A., Raine, T., Hendy, P.A., Smith, P.J., Limdi, J.K., Hayee, B., Lomer, M.C.E., Parkes, G.C., Selinger, C., Barrett, K.J., Davies, R.J., Bennett, C., Gittens, S., Dunlop, M.G., Faiz, O., Fraser, A., Garrick, V., Johnston, P.D., Parkes, M., Sanderson, J., Terri, H., IBD guidelines eDelphi consensus group, Gaya, D.R., Iqbal, T.H., Taylor, S.A., Smith, M., Brookes, M., Hansen, R. & Hawthorne, A.B. (2019). British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut, 68: s1-s106. Doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484.

Link to Publication: https://gut.bmj.com/content/gutjnl/68/Suppl_3/s1.full.pdf

Kuenstner, J.T., Naser, S., Chamberlin, W., Borody, T., Graham, D.Y., McNees, A., Hermon-Taylor, J., Hermon-Taylor, A., Dow, C.T., Thayer, W., Biesecker, J., Collins, M.T., Sechi, L.A., Singh, S.V., Zhang, P., Shafran, I., Weg, S., Telega, G., Rothstein, R., Oken, H., Schimpff, S., Bach, H., Bull, T., Grant, I., Ellingson, J., Dahmen, H., Lipton, J., Gupta, S., Chaubey, K., Singh, M., Agarwal, P., Kumar, A., Misri, J., Sohal, J., Dhama, K., Hemati, Z., Davis, W., Hier, M., Aitken, J., Pierce, E., Parrish, N., Goldberg, N., Kali, M., Bendre, S., Agrawal, G., Baldassano, R., Linn, P., Sweeney, R.W., Fecteau, M., Hofstaedter, C., Potula, R., Timofeeva, O., Geier, S., John, K., Zayanni, N., Malaty, H.M., Kahlenborn, C., Kravitz, A., Bulfon, A., Daskalopoulos, G., Mitchell, H., Neilan, B., Timms, V., Cossu, D., Mameli, G., Angermeier, P., Jelic, T., Goethe, R., Juste, R.A. & Kuenstner, L. (2017). The Consensus from the Mycobacterium avium ssp. Paratuberculosis (MAP) Conference 2017. Frontiers in Public Health, 5: 1-5. Doi: 10.3389/pubh.2017.00208.

Link to Publication: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29021977/

McNees, A.L., Markesich, D., Zayyani, N.R. & Graham, D.Y. (2015). Mycobacterium paratuberculosis as a cause of Crohn’s Disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterology Hepatology, 9(15): 1523-1534. Doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1093931

Link to Publication: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4894645/pdf/nihms787513.pdf

Swift, D. (2019). MAP: Just a Suspect or Proven Perp in Crohn’s? – Debate over mycobacterium paratuberculosis as major CD cause mirror Helicobacter pylori saga. AGA Reading Room, Medpage Today. Published online 05/09/2019.

Link to Publication: https://www.medpagetoday.com/reading-room/aga/lower-gi/79712

Wilkins, T., Jarvis, K. & Patel, J. (2011). Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease. American Family Physician, 84(12), 1365-1375.

Link to Publication: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/1215/p1365.html