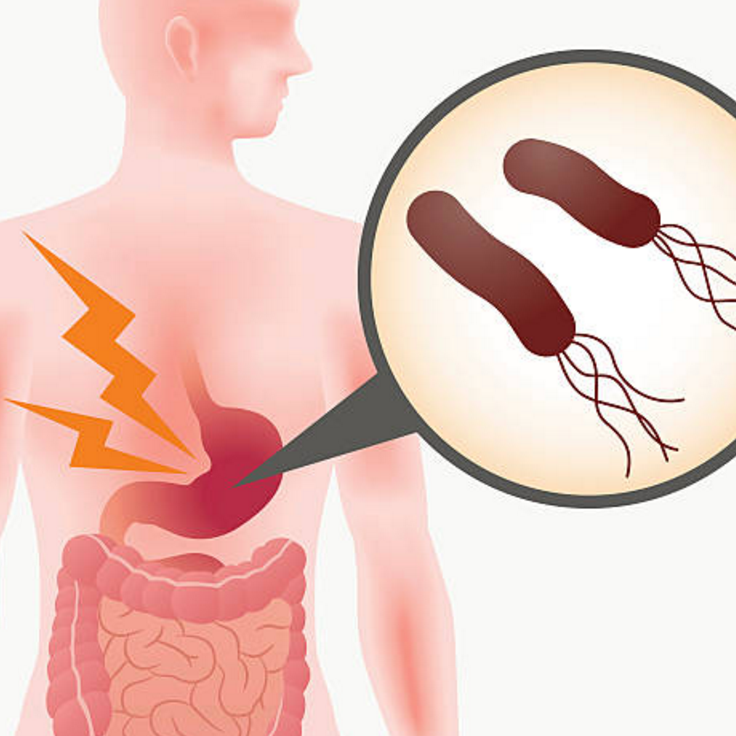

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral-shaped bacterium that infects well over 30% of the world’s population. In some countries it infects more than 50% of the population3. This is, therefore, one of the most common human bacterial infection.

CDD discovery

Following confirmation in the 1980s that H. pylori caused peptic ulcers, the Centre for Digestive Diseases Medical Director and Founder Doctor Thomas Borody, developed the first therapy to fight H pylori and cure peptic ulcers1,2. This went on to become the gold standard treatment globally.

The World Health Organisation has declared the bacteria to be a Class 1 carcinogen (meaning the bacterium produces cancer in humans). It invades the mucosal lining of the stomach and is the cause of up to 80% of duodenal and up to 60% gastric ulcers and has also been associated with gastric cancer and lymphoma3.

Transmission

Despite intense investigation into the spread of H.pylori, the precise mode of transmission remains unclear. There is some evidence to suggest that H. pylori is transmitted from person to person via the faecal-oral route, yet the transmission mode remains unclear. At this stage the oral-oral or faecal-oral transmission routes are the most likely. Most H. pylori infections occur in childhood. Crowded living conditions, poor sanitation, poor personal hygiene and a poor water supply correlate with higher rates of infection (which can approach 80% of the population in the developing world).

H.pylori infects both genders equally.

Symptoms

The majority of people with H.pylori are asymptomatic but symptoms of infection can include burning pain in the upper portion of the abdomen, indigestion, nausea, vomiting, burping, loss of appetite.

Complications

H.pylori has been strongly linked to the development of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Eradication of H.pylori can prevent ulcers forming. Patients presenting with ulcers should be tested for H.pylori and receive treatment because eradication of this bacterium in patients with pre-existing ulcers not only cures ulcer disease, but also prevents most recurrences. Whilst the presence of H. pylori in the stomach induces a chronic active inflammation in almost everyone infected, fewer than 10% of individuals colonised with H. pylori develop serious disease or complications such as peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer or mucosa-associated-lymphoid-tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

There is strong evidence that H.pylori contributes to the development of gastric cancer. Many factors are likely involved to cause cancer as only a tiny proportion of patients with H.pylori go on to develop gastric cancer. Diet low in fruit/vegetables, smoking, age and a high salt intake also increase the risk of gastric cancer independent of H.pylori infection. However, of all these factors, it is H. pylori infection which is most closely associated with stomach cancer. Hence, due to its known association, all patients with H. pylori should be considered for treated.

H.pylori infection can also lead to the development of a condition known as mucosa-associated-lymphoid-tissue (MALT) lymphoma, a type of cancer of the stomach. Treatment and eradication of H. pylori infection can result in regression of the malignancy in up to 75% of cases.

Diagnosis

There are many different tests used to diagnose H. pylori infection. Tests for H. pylori can be invasive requiring upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (gastroscopy) and based on the analysis of gastric biopsy specimens, or non-invasive using test strips and breath tests3.

Gastroscopy – A gastroenterologist may perform a panendoscopy (also known as a gastroscopy). This examination requires the patient to be sedated before an endoscope equipped with miniature video equipment is inserted through the mouth and down into the oesophagus. The gastroenterologist can then take a biopsy (sample of tissue) for pathological testing to determine the presence of pylori infection. Histological diagnosis, whereby this tissue sample is examined under a microscope, is the gold standard. As well as confirming the presence of H. pylori, the pathological state of the stomach lining can be determined and defined as acute or chronic gastritis, atrophy, abnormal cells (metaplasia or dysplasia – precancerous changes), Barrett’s oesophagus, or even lymphoma / malignancy.

A rapid urease test may also be used to prove infection. These tests are known to achieve very high levels of accuracy.

A culture of H. pylori can be carried out on such a tissue biopsy to determine the sensitivity of particular antibiotics. This is of most importance in patients who had failed the usual treatment and still carry the infection. In these individuals the sensitivity of H. pylori is tested to ensure the most appropriate treatment is commenced.

Urea Breath Tests – Breath testing provides a rapid, non-invasive way of detecting the presence of active infection and is often used to check whether eradication has been successful. This test uses a sample of exhaled breath to determine infection.

The principle of this test relies on the ability of the bacteria to convert a compound called urea to carbon dioxide. Specially labelled urea is given by tablet form orally and the exhaled breath is tested for labelled carbon dioxide. These tests are very accurate and easy to perform.

Serology – Patient’s blood may be screened for the presence of antibodies to H. pylori indicating an immune response to the bacteria. These tests are slightly less accurate than other available tests and do not discriminate between current infection and recent exposure. In those patients where the gastric lining has changed to the precancerous form of intestinal metaplasia, neither biopsy nor urea breath tests are able to be used as there are very few bacteria present. However, serial serology from antibody concentrations can be used as follow-up post treatment of H. pylori infection.

Stool Antigen Test – This can be quite an accurate test and is being used more frequently.

First Line Therapy

Treatment for H. pylori focuses on eradicating the bacteria from the stomach using a combination of organism-specific antibiotics with an acid suppressor and/or stomach protector. The use of only one or two medications to treat H. pylori is not recommended. Different countries have different approved treatments for H. pylori. At this time, a proven and effective treatment in Australia is a 7-day course of medication called Triple Therapy comprising two antibiotics, amoxicillin and clarithromycin, to kill the bacteria together with an acid suppressor to enhance the antibiotic activity. This regimen of triple therapy reduces ulcer symptoms, kills H. pylori and prevents ulcer recurrence in around 70% of patients but its efficacy is slowly falling.

With the use of antibiotics to treat so many patients with various conditions it has become more difficult to treat H. pylori due to increasing occurrence of antibiotic resistant strains. As a result, up to 35% of patients fail the first line therapy.

Second line & subsequent therapies for resistant H. pylori

At the Centre for Digestive Diseases, following treatment failure and at times upon initial therapy, a combination regime is designed specifically for the patient often guided by the bacteria’s antibiotic sensitivity profile. Using these tailored treatments our gastroenterologists can treat even resistant H.pylori.

Research

At the Centre for Digestive Diseases, we are especially interested in developing ‘salvage’ or ‘rescue’ therapies which are used to treat patients who have failed other standard treatments. These treatments use varying combinations of three or more anti- H. pylori drugs teamed with a medication to stimulate the immunity of the gastric lining.

Contact Details

If you would like to see one of our Gastroenterologist to discuss your condition and be considered for treatment, please refer to the following link for instructions on how to become a patient at the Centre for Digestive Diseases: https://centrefordigestivediseases.com/how-to-become-a-patient/.

References and Further Reading

1 Borody, T.J. (2016). Development of novel therapies for gut dysbioses. Open Publications of UTS Scholars (OPUS). Identifier: http://hdl.handle.net/10453/52985

Link to thesis: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/52985/6/01front.pdf

2 Eslick,G.D., Tilden, D., Arora, N., Torres, M. & Clancy, R.L. (2020). Clinical and economic impact of “triple therapy” for Helicobacter pylori eradication on peptic ulcer disease in Australia. Helicobacter, 25(6). Doi: 10.1111/hel.12751

Link to article: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/hel.12751

3Yaxley, J. & Chakravarty, B. (2014). Helicobacter pylori eradication – an update on the latest therapies. Australian Family Physician, 43(5): 301-305.

Link to article: https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2014/may/helicobacter-pylori-eradication/